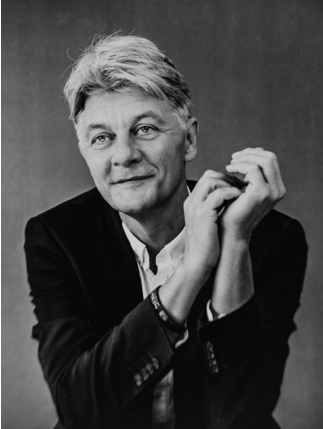

Chris Keulemans (1960) is a writer, journalist, teacher and moderator based in Amsterdam, where he founded and/or ran three cultural centres. In the meantime, he published six

books of fiction and non-fiction, next to essays and articles about war, literature, migration, urban issues, cinema and music. For work and friendship, he has always traveled across Europe

and beyond. He calls Sarajevo his second hometown. Over the past years, on behalf of the network Trans Europe Halles, he visited and advised emerging cultural spaces from Dnipro to

Lisboa. After publishing a book of essays and travel stories on the art of hospitality last year, he is now working on a book about resistance.

Chris Keulemans, interview exclusively for The Bridge

Jean Monnet, who has been called “The Father of Europe”, said once that, if he were to restart its construction, he would have started from culture. What is for you such a thing as the European culture?

It’s always a bit disappointing when leading political figures discover the value of arts and culture only afterwards. Even the fact that Monnet found that he had to mention culture specifically, while his idea for the European Union was built on coal and steel, demonstrates how he regarded the arts and the industry as distinctive and separate domains. While anyone who lives in the cultural world could have told him that no serious community could ever be based on such separations.

And what would the EU have looked like if Monnet had actually started from culture? In the early 1950’s, he would have encountered an artistic landscape that was shell-shocked, fragmented, traumatized, radical, betrayed by history and determined to break with traditions. All that the scattered artists and movements across the continent might have in common would be the contempt for coherence, union and harmony. It would be intriguing to see how Monnet developed his ideas if he had seriously confronted the disillusionment of Heinrich Böll, the unspoken horror underneath Alain Robbe-Grillet cinema, the bleak life on the margins of society in De Sica and Pasolini, the fundamental loneliness in Ingeborg Bachmann’s writing, Giacometti’s broken human figures, Primo Levi’s accounts of the holocaust. European culture at the time was anything but a force of hope and togetherness.

We are witnessing a rise of nationalist extreme right in our continent, moreover in the founding countries of what today is the European Union. How do you see the role of cultural identity in the conception of this ultra-nationalism?

As a semi-literate, narcissistic and frightened jumble of lies and self-delusion. Perfect example: how Italy’s neo-fascist prime minister Giorgia Meloni glorifies the icons and the ethics of Tolkien’s Middle-earth. She posts proud images of herself posing next to an image of Gandalf on his horse, as if to say: this is my spiritual master, my source of knowledge and culture. Coming from the ruler of a country drenched in real, incomparable history and art, such a public image is both hilarious and terrifying. And typical of a new wave of ultra-nationalism that creates – as a part of its isolationist, xenophobic and ultimately self-destructive policies – a cheap utopia, based on evil misinterpretations of some badly understood episodes in the national history, while all the time pushing its voters deeper into insecurity and ruin, at the expense of the even more unfortunate Other.

The Germans were considered the most cultivated people of Europe, the people of poets and philosophers and musicians. How it can be explained that this did not prevent them from supporting massively the Nazi regime? Does it demonstrate that the dream of the Enlightenment about culture as a factor of emancipation turns out to be a nightmare?

I certainly don’t feel qualified to be the next one pondering the question what happened in Germany. But it might be useful to rephrase this question once we take a closer look at this image of the Enlightenment that we here in Western Europe have so carefully and proudly created.

The age of Enlightenment opened up an era of emancipation on many levels in the nations where it was cultivated. It was also, from the very beginning, a period of nightmare. It coincided with the high tide of French, British, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese empire and colonialism. Emancipation here was oppression there. The cruelty, exploitation and the refusal to see the Other as human was the exact flipside of what the Enlightenment stood for on this side of the world. Apparently, the one could not exist without the other. The wealth to live and think in freedom could not exist without denying that same freedom to others. The execution of brutal power and domination elsewhere created the space and the facilities for the emancipation that so many people here desired.

So, while I am not in the position to comment on the roots of the Nazi horrors, I do appreciate that we live in a time where the benefits of Enlightenment are not just sanctified, but also placed in the context of a culture where they were graciously extended to some and violently refused to others.

What could be the role of culture for a better Europe?

Fortunately, I have not become a Minister of Culture, which would have forced me to reply in high-minded, confident and empty phrases to such desperate questions. Desperate, because they will always be asked by the right people, the people who hold deep and sincere beliefs about the liberating power of art and beauty, the people who look around in despair and cannot understand why those in power still haven’t learned that the solution to all our problems lies not in destruction but in creation. People like you and me.

Instead, I am just a writer and journalist who travels across this continent and sees how the changes towards a better, more just and more open society are being created, sometimes by force, sometimes by accident, by artists and activists who recognize that beauty cannot exist where rights are not accessible to all. For all too long, maybe, this continent has nourished a culture that reserved its icons of beauty for the few, that somehow equated art with power and money. Today, and better late than never, we might be witnessing a cacophonic, uprooted, multi-layered, defiant and rebellious climate of arts and culture where everyone can find, however temporary, a place to belong.