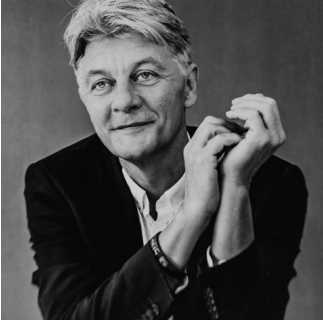

Aidan Hehir is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Westminster. His research interests include transitional justice, humanitarian intervention, and statebuilding in the Balkans. He is the author/editor of ten books and co-editor of ten books. His poetry has been published in a number of magazines and he has collaborated with a number of recording artists on spoken word poetry

pieces including Hand of Stabs and Broken Banjo. A play he co-wrote with Stephen Mellon titled A Wake was staged at the Southwark Playhouse in London in 2018, and their play A Leap of Faith won the 2020 “Best Play” and “Best Original Script” at the 2020 Duncan Rand festival. We are publishing the text that he read in the festival polip, an exerpt from his book The Flowers of Srebrenica.

“Americans are so stupid!”

The forests gradually move closer to the road. Soon we are driving through thick walls of green. The view becomes hypnotic. We’ve not spoken for some time. I feel like I’m going to slip into a hallucinogenic state. I decide to break the silence before we crash.

“My father was a tour guide like you,” I say, “in Ireland.” “Ok,” Mustafa says. “He drove American tourists around the west coast,” I say. “Always Americans.” “Yes,” he says.

“Have you heard of leprechauns?” I ask. “Of course,” he says, “the little magical dwarves.” “Yes,” I say. “Well, the Americans always wanted my father to show them leprechauns. He’d explain they weren’t real, but they were really disappointed to hear this. Always. So eventually he arranged for this small guy outside a village in County Galway to dress up as one. My father would ring ahead, then park the car by this particular field. They’d get out to look at the view – my Da and the Americans – and then the guy dressed as a leprechaun would run across the field, singing, and skipping. The Americans loved it.”

Mustafa says nothing. I look out the window. I decide I have to finish the story. “So, one time,” I say, “the leprechaun guy got really drunk at a wedding and didn’t put the costume on properly. When he came running out from behind the stone wall, still carrying a bottle of Guinness, his trousers fell down, he tripped over and landed in a heap with his bare arse in the air. He sprained his ankle. He was lying there on his back, half-naked, screaming in pain, roaring out these foul curses.” “Yes,” says Mustafa smiling.

“And one of the Americans, this woman, says, ‘Oh my gosh! Everything I’ve ever read about Ireland is so true.’” He laughs loudly. “Americans are so stupid!” he says. “Yes,” I say. We both laugh. “Americans!” he says again, “so stupid!” “Yes,” I say.

[…]

Mustafa leads me into another room. I’m very thirsty. I can see the heat is getting to Mustafa too. We left our bottles of water in the car.

There is a bank of TV screens. I put on headphones and play the first video. Its 1 minute and 32 seconds long. It shows General Mladic talking to Colonel Karremans. Mladic threatens him and his soldiers. Karremans looks terrified.

I play the second video. Its 46 seconds long. It shows Mladic and Karremans at the UN base. The Dutch troops are leaving. Mladic is very happy. He wishes Karremans well and presents him with a wrapped bottle of wine. “For my wife?” laughs Karremans. They all laugh.

My feet are throbbing. I’ve got a headache. There is a strange taste in my mouth. I play the third video. It shows the Dutch troops leaving Srebrenica. They go to a base outside Zagreb. They have a party. They dance in a conga line. They sing. Crates of Heineken are loaded from trucks.

I’ve never seen this before. Mustafa stands beside me. The party descends into a churning mass of gurning faces and intertwined limbs.

I play the fourth video. Karremans is giving a press conference. He defends his decisions. He denies reports that a massacre occurred. He criticises those who don’t understand what ‘really’ happened. “There were no good guys, no bad guys,” he says.

The video of the troops dancing and drinking is on repeat to my left. I see the school children walk past the window outside. At the other end of the room, I can see the video of Hasan Nuhanović. To my right I see Mladic and Karremans laughing. “No good guys, no bad guys.” The room is like an oven. I stare at the screens. My head is throbbing. I’ve never been so thirsty.

Nuhanović. Mladic. Karremans. The dancing soldiers. “No good guys, no bad guys.”

I look around. Maybe there is a tap somewhere. Maybe Mustafa has stored water somehow. He’s standing watching the soldiers dancing. A pallor of sweat across his brow.

Nuhanović. Mladic. Karremans. The dancing soldiers. “No good guys, no bad guys.”

Suddenly I feel like something pops behind my eyes. These fucking people! Mladic. Karremans. The dancing soldiers. What they did and didn’t do.

But why now I think? I’ve spent twenty years reading about atrocities like this. Writing. Thinking. Researching. Criticising. Suggesting.

But now it feels like some force is laughing at me. “Now as you stand here, in front of this, do you see that you and all your work, and your words are nothing?”

I pull off the headset. “Fuck this,” I say. A trickle of sweat runs down my face. I turn to Mustafa. He looks shocked.

“What the fuck is this shit?” I say. “What?” he asks. “All of this” I say pointing, “this fucking scandal!” “Ok,” he says, “I know.” “Look at them! They are the UN!” I shout, “The fucking UN!” “Yes, I know,” he says. “Threatened by that little bastard Mladic!” I say. “The UN! Told what to do by that murderer! Ordered to turn over the civilians!” “Ok,” says Mustafa.

The screens keep playing the images. “And what’s this party shit?” I say. “A party!” I say again. “Yes,” he says, “but…” “They’re having a fucking party! I mean…” “I know,” he shouts at me, “I know!” Anger flashes across his eyes. Then he exhales slowly. He turns to the screens. He points. “These soldiers,” he says calmly, “I do not believe they are happy because my people are killed.” He looks at me. “They are young. They believed they were going to die. They are only happy to be alive.” We watch the soldiers. “They are happy to have escaped,” he says, “that is all.” Maybe, I think.

“But the Colonel,” I say, “and all those people back at the UN in New York…They could have stopped this,” I say, “and they should have stopped this! They….” “Yes,” he says angrily, “I told you I know!”

He walks away from me. He stops and turns. He is crying. “You see those boys in the video,” he says, “shot in the woods?” “Yes,” I say “They were two, three years younger than me then.” He takes off his glasses. “I think about these boys often,” he says.

I look at him. The soldier who has stayed sane because he’s not afraid to cry. He strokes his forehead. Rubs his eyes.

I think I should hug him. Or put my arm on his shoulder. Something. Do it, I tell myself, he’s crying in front of you.

We stand awkwardly. He puts his glasses back on. He walks towards the door and gestures. I follow.

(…)

I must be thirsty. I think I am. I’m feeling dizzy, delirious. My mind starts to crackle and distort. I must walk back to Mustafa.

There is a sound in the air like something I’ve heard but never out loud. It strains and it pulses. I hear it in snatches and echoes and catch it in glimpses.

The sound rises and falls as I walk. And the sun beats down. The air sings out and the tree’s dance. The ground seems to shake beneath my feet, and the air sings louder and all around is silence and I don’t think I can breathe, so I inhale loudly and still the sun beats down.

The graves stand as I pass, too many to count, too many names to read, too many… and I am not enough to read them.

The sound continues to ring all around. Can anyone hear this? I ask. I’m glad I can, and I think I want to hear this now, and forever, and ever, and never forget. And only remember, the sound, whatever it is, and wherever it comes from and whoever it’s calling to. And I know it’s not calling just to me.

And I feel something, like a touch or a force passing.

I think of all that lies buried – still, and silent waiting, judging, watching us as we stand here – and I think I’ve brushed against it as I’ve passed.

And I think all this should be told to all those who do not know. But I think it won’t be, though many will try. And when it’s not what will be the toll?

I think of all those here rising up – taking form walking out and onwards maybe in another world to do battle and tell their story – and brushing against me as they pass.

And I know these touches are not real, and can’t be felt, but maybe, someday, they will be.

Translated by Gazmend Bërlajolli