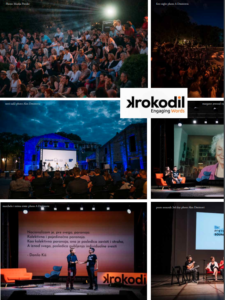

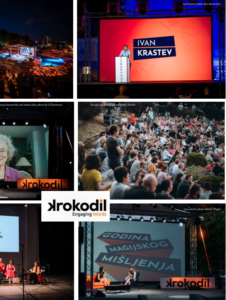

Ariana Harwicz was born in Buenos Aires in 1977, and since 2007, she is living in the French countryside. Her books have been published in most of the European languages. “Harwicz excels at tackling taboos around female desire, filial loyalty, a lack of maternal instinct and even incest. Moreover, her prose, thanks in part to the razor-sharp translation, is completely addictive”, wrote about her the British scholar Ellen Jones in The Guadian. We are publishing the first chapter of her first novel, Die, my love, longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker International Prize. This exerpt was read by the author during the KROKODIL festival.

I lay back in the grass among fallen trees and the heat of sun on my palm felt like a knife I could use to bleed myself dry with one swift cut to the jugular. Behind me, against the backdrop of a house somewhere between dilapidated and homely, I could hear the voices of my son and my husband. Both of them naked. Both of them splashing around in the blue paddling pool, the water thirty-five degrees. It was the Sunday before a bank holiday. I was a few steps away, hidden in the underbrush. Spying on them. How could a weak, perverse woman like me, someone who dreams of a knife in her hand, be the mother and wife of those two individuals? What was I going to do? I burrowed deeper into the ground, hiding my body. I wasn’t going to kill them. I dropped the knife and went to hang out the washing like nothing had happened. I carefully pegged the socks to the line, my baby’s and my man’s. Their underwear and shirts. I looked at myself and saw an ignorant country bumpkin hanging out the laundry and drying her hands on her skirt before returning to the kitchen. They had no idea. Hanging out the clothes had been a success. I lay back down among the tree trunks. They’re already chopping wood for the cold season. People here prepare for winter like animals. Nothing distinguishes us from them. Take me, an educated woman, a university graduate – I’m more of an animal than those half-dead foxes, their faces stained red, sticks propping their mouths wide open. My neighbour Frank a few miles away, the oldest of seven siblings, fired a shotgun into his own arse last Christmas. What a nice surprise it must have been for his pack of kids. But the guy was just following tradition. Suicide by shotgun for his great-great-grandfather, great-grandfather, grandfather and father. At the very least, you could say it was his turn. And me? A normal woman from a normal family, but an eccentric, a deviant, mother of one child and with another, though who knows at this point, on its way. I slowly slide a hand into my knickers. And to think I’m the person in charge of my son’s education. My husband calls me over for a beer under the pergola, asks, blonde or dark? The baby appears to have shat himself and I’ve got to go and buy his cake. I bet other mothers would bake one themselves. Six months, apparently it’s not the same as five or seven. Whenever I look at him I think of my husband behind me, about to ejaculate on my back, but instead turning me over suddenly and coming inside me. If this hadn’t happened, if I’d closed my legs, if I’d grabbed his dick, I wouldn’t have to go to the bakery for cream cake or chocolate cake and candles, half a year already. The moment other women give birth they usually say, I can’t imagine my life without him now, it’s as though he’s always been here. Pfff. I’m coming, baby! I want to scream, but I sink deeper into the cracked earth. I want to snarl, to howl, but instead I let the mosquitoes bite me, let them savour my sweetened skin. The sun deflects the silvery reflection of the knife back to me and I’m blinded. The sky is red, violet, trembling. I hear them looking for me, the filthy baby and the naked husband. Ma-ma, da-da, poo-poo. My baby’s the one who does the talking, all night long. Co-co-na-na-ba-ba. There they are. I leave the knife in the scorched pasture, hoping that when I find it next it’ll look like a scalpel, a feather, a pin. I get up, hot and bothered by the tingling between my legs. Blonde or dark? Whatever you’re having, my love. We’re one of those couples who mechanise the word ‘love’, who use it even when they despise each other. I never want to see you again, my love. I’m coming, I say, and I’m a fraud of a country woman with a red polka-dot skirt and split ends. I’ll have a blonde beer, I say in my foreign accent. I’m a woman who’s let herself go, has a mouth full of cavities and no longer reads. Read, you idiot, I tell myself, read one full sentence from start to finish. Here we are, all three of us together for a family portrait. We toast the happiness of our baby and drink the beers, my son in his high chair chewing on a leaf. I put a finger in his mouth and he shrieks, biting me with his gums. My husband wants to plant a tree for the baby’s long life and I don’t know what to say, I just smile like a fool. Does he have any idea? So many healthy and beautiful women in the area, and he ended up falling for me. A nutcase. A foreigner. Someone beyond repair. Muggy out today, isn’t it? Seems it’ll last a while, he says. I take long swigs from the bottle, breathing through my nose and wishing, quite simply, that I were dead.

Translated by

Sarah Moses & Carolina Orloff