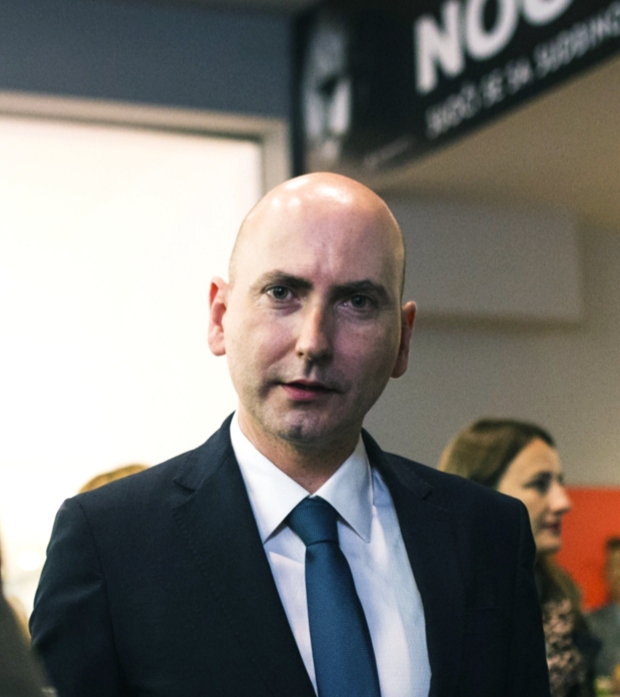

Interview by Amila Kahrović-Posavljak

Andro Martinović – Graduated World Literature and Film and TV Directing. Director of the Montenegrin Cinematheque. Professor at the UDG and Faculty of Visual Arts. Author of several award-winning short films, which are screened in the competition selection at more than twenty prestigious international film festivals. Coauthor of the documentary “Montenegro and The Great War”. He published articles in newspapers and professional journals. “Neverending Past” is his first feature film, supported by the Ministry of Culture of Montenegro and Film Center Serbia. The project was developed in cooperation with CineLink Industry Days – Sarajevo Film Festival.

In the Balkans there are currently two opposite concepts of culture, the nationalist and the one that represents itself as anti-nationalist. What could be their prospective, generally, in the role of culture in the society?

- Martinović: You are right on the money. I am going to use the medical terminology, because I truly do see nationalism as an incurable illness. Let me remind you that Kiš had described it as a collective and individual paranoia. The apotheosis of the national in culture is not unfamiliar to our people, although, as a rule, resulting from that notion there are often works considered to be rather irrelevant in aesthetic terms. I am inclined to believe that this model of culture is based on temporal effect intended to happen right here and now. The purpose of nationalistic products in culture is simply to strengthen the homogenization in the political context. On the other hand there are platforms with reference systems which can be limiting to a certain extent. If you ever had style guidelines as a set of certain rules which one needs to follow in order to be accepted, today this dictate originates from ideological reasoning.

Do you think that this kind of opposed cultural concepts deepens the divisions? If so, what would be a solution?

In the sociology of culture this issue has been subject to scrutiny, as well as the idea of bridging cultural distances. I believe, above all, that we should stick to the principles of modern, civil society. The path to reach a higher level of social cohesion is set through the educational system and culture in the broadest sense, which also implies modern hospitals, parks and playgrounds; through the sense of justice and solidarity.

How do you see the incompatibility between Aristotle’s idea that the art is the most precious value because it is a value in itself, and the fact that there are artists who commit horrible crimes and embrace fascist ideologies, such as it happened in World War Two, or for example the writers who were shooting on Sarajevo under the siege?

In his “defence” of art, Aristotle started with the assumption that the art sublimates the empirical human being. The question, of course, is whether the work of art can be exempted from the shadow cast by its author. Sometimes the controversy about the author may contribute to his fame, although the justification of tragic crimes by him is denounced. If manuscripts do not burn (Bulgakov), people do.

From your personal experience, as a filmmaker, what is the prospective of culture in the countries of former Yugoslavia and, after all, Balkans?

Culture depends on the situation in the society. If we take a look to the past, we can see that the traces from distant times are the closest in what is really our cultural heritage. In order to have the appropriate development we need continuity, because time lost is a permanent handicap. Let us alter what needs to be altered, which is similar in all of former Yugoslav countries. I do strongly believe in common cultural space and in our joint struggle.

It seems that in the global context of art we are associated with only a few kinds of subjects. Before the war it was the sort of image given by socialist realism in the movies, now it seems that our whole artistic experience must fit into anti-war poetics. How do you see this issue? Are there any expected subjects we must write about in order to be recognized abroad?

I touched that issue briefly before. There are, of course, subjects often revisited by art. Cioran had opined that we experience two climaxes: orgasm and despair. The difference is that the former lasts only for a moment and the latter the whole life. The danger truly lies within that horizon of expectations. An image once formed on an issue whose topics are reserved for one ambience and whose manner is plausible to treat changes slowly, only when it reaches a certain level of saturation. Whatever leaves that frame, usually stays out of focus. As a rule, artistic practice should confirm an established opinion.

There is always some sort of discordance between the role of art as such and the role of art as a form of approaching the Other. How is it perceived in our cultural circles?

Communication is the foundation of art, with oneself and with the Other. It is like a message bound to reach its destination sooner or later. It is a reflection of reality, of the visible and the invisible one. Let us take, for example, Kafka or Van Gogh, for whom one feels that they are always writing the pages of their own personal, intimate journal. Two of the most important Kafka’s texts start with the waking up of the character, but waking into a nightmare.

Can culture help in the relations with other nations and cultures?

When everything else is put aside, culture remains. It is the most reliable testament of the world, sometimes even as a hint of it; as the philosopher from Stagira might have said, it is what we could have become and what we should have been. It is paradoxical, therefore, that we see the cultural singularities as the reason for mutual destruction.

What about the critical aspects of a culture? Have we become a bunch of closed societies who expect culture to always criticize the Other and never asks inconvenient questions about our own nations?

There is a belief that art must be engaged, meaning that it should be critical towards the establishment, the government, various anachronisms… More often than not, whether consciously or not, it leads to the instrumentalization of art. It is a psychological phenomenon that we are bothered with another person’s features reminding us of ourselves. When reconsidering, one should start with oneself; one should discard the sense of self-exclusivity; and only then could reconsider the collective or national.

Regarding discussions on religious freedom in Montenegro and the laws related to that, are there any artists who raised their voices, and in what way?

Voices related to this could seldom be heard. There are, however, social developments which are calling for unequivocal expression. The phenomenon of church protests, I feel, is such an example.

These protests have essentially a political character. Many a time, due to actions of a certain church outside of the legal framework, the country is facing serious challenges. Other than religious, there are civil laws to be followed and respected. This is why the resistance to changes which are bound to happen is expected.

Those many in such events that look like processions are influenced by dissatisfaction generating from a growing sense of social inequality. Having said that, the manifestations organized by the Church remind me of scenes from Vargas Llosa’s novel “The War of the End of the World”, where whole families follow the Advisor and his dangerous sermons blindly.

Are young people and their culture related to art now as they used to be for decades of the twentieth century? If not, what do you think is the reason?

The answer to this question lies in adequate research. Based on my experience working with younger generations, I can voice my opinion that the consequences of tectonic movements in the educational system are very visible. Even in art schools there are students with no basic knowledge of art history. This, however, does not imply that there is no interest in the art, quite the contrary. And indeed, if we have lost something, it is the status that the art should have in the society, that feeling for which the artistic event is something of essential importance.

In the end, what do you see as the basic role of an artist nowadays?

Never give up, even if it is the only way to keep one’s peace.

Your movie is (was) nominated for Oscar and gained great success. What are your further plans?

I am working on preparation for two movies. One is documentary, about Montenegrins participating in creating the Turkish football club with the most trophies, “Galatasaray”, and the unlikely friendship of two sovereigns, Montenegrin and Turkish. The other is about the Montenegrin prince Danilo I, which in a certain sense can be a film about present Montenegro. It is not so much about delusive historical analogies, but about the crucial importance of heritage of a person dedicating his life to the idea of creating a modern country. In the background of that struggle there are the intrigues, conflicts, resistance. Danilo dealt with them the only way he could, in the spirit of times he had lived in, musing on a different fate of the nation whose prince he was, with the iron will to subordinate everything to the highest political cause… And that is what it has always been freedom of will.