Gonca Özmen was born in Burdur, Turkey, in 1982. She studied English Language and Literature at Istanbul University, receiving an MA in 2008 and a PhD in 2016. Her first poem was published in 1997 and in 1999 she received the Ali Rıza Ertan Poetry

Prize. Her first collection Kuytumda (In My Nook, 2000) won the Orhon Murat Arıburnu Poetry Prize and in 2003 she received Istanbul University’s Berna Moran Poetry Prize. Her second collection Belki Sessiz (Maybe Silent) appeared in 2008 and published in

German, translated by Monika Carbe, in 2017. Second edition of Belki Sessiz in German was published in 2018 with additional translations by Barbara Yurtdaş. A selection of her poems in English, The Sea Within, translated by George Messo, appeared in 2011. She

is a member of the advisory board of Bursa Nilüfer International Poetry Festival and the magazine, Turkish Poetry Today, published annually by Red Hand Books, England. She is also a member of the Three Seas Writers’ and Translators’ Council (TSWTC) in Rhodes, Greece.

Culture/art can be defined as one of the most influential ways to connect us with the Other. Culture/art is still male-dominated. Art, in particular literature and painting, holds the power of representation, and it is through representations that we know the world. In ekphrastic poetry, words and images come together as means of ideology, which is itself a system of representations. Thus the politics of the representation of the female, both in visual and verbal western phallocentric art should be discussed in depth. Its political, social and cultural codes exercise power over the construction of femininity. However the patterns of power and the value of representation in art/history are rewritten by women poets in order to both expose and redefine its gender-specific system of values and criteria of significance and liberate the female body.

Whitney Chadwick observes that: “In the early 1970s, feminist artists, critics, and historians began to question the apparently systematic exclusion of women from mainstream art. They challenged the values of a masculinist history of heroic art which happened to be produced by men and which had so powerfully transformed the image of woman into one of possession and consumption”. Since the 1970s, contemporary women poets have produced their own meanings in their works, challenging and disrupting the ways women are represented within mainstream cultural production, the power to determine what is ‘high’, ‘great’ or ‘significant’ art being, moreover, still in the hands of male-dominated institutions. They try to find a way out of the inscriptions of masculinity in art/history by reacting against these codes of representation dominated and controlled by men. In her important study Twentieth-Century Poetry and the Visual Arts, Elizabeth Bergman Loizeaux argues, “Feminist ekphrasis recognizes that a woman’s place as viewer is established within, beside, or in the face of a male-dominated culture, but that the patterns of power and value implicit in a tradition of male artists and viewers can be exposed, used, resisted and rewritten.” Contemporary women poets indeed criticize the male tradition and in their re-working of canonical paintings by men seek to empower the passified and muted female models in paintings.

In their ekphrastic poems, some women poets choose the paintings of ‘great male masters’ and restore to the silent and passive female models their voices thus transforming them into speaking subjects. W. J. T. Mitchell notes that “The ekphrastic poet typically stands in a middle position between the object described or addressed and a listening subject who (…) will be made to ‘see’ the object through the medium of the poet’s voice.” Thus, these women poets invite us, the readers, to become implicated in the process of recovering the stories of the muted female models, who talk back to the men who painted them.

The poets directly respond to well-known paintings by men as cultural intertexts and question the absolute authorities of these canonical works from feminist perspectives. They try to free themselves and the female (body) from the authority of both these great male masters, and the patriarchal tradition they represent, by adopting a subversive dialogic method. It can, of course, be said that paintings like literature are arbitrary and indeterminate in their meaning. The concept of intentional fallacy, moreover, tells us that it is impossible and also undesirable to reconstruct the intention of the writer/painter. The paintings might thus not only be said to contain contradictory ideas, but they can also be interpreted in many different ways. However, the female poets are certainly justified in their attempt to deconstruct what they interpret as male dominated codes of representing the female body in portraits and nude paintings. Both traditions in painting have indeed been dominated by men and inevitably shaped to some extent at least, or as art historians tell us to quite an extent, by their codes.

The female poets who adopt this technique try to deconstruct the cultural hegemony of phallocentric ideologies in the field of art by returning to the canonical artworks of the past, rewriting them in order to displace the image of the silenced women. They regard the phallocentric art tradition as a force to be resisted and demand revisions in the interpretation and reconceptualization of art. What is a central concern in their poetry is the critique of the ideological male dominated representation of stereotypes of femininity as well as the deconstruction of the gendered hierarchy of art. The women poets intervene in the male art tradition and insert a feminist perspective with the object of change in gender politics in both art and society.

The word ‘ekphrasis’ derives from the Greek ‘phrazien’, meaning ‘to tell, to pronounce, or to declare’. The prefix ‘ek-’ is Greek for ‘from, or out of’. Thus the word literally means ‘to speak out, to describe, to tell someone about something, to depict vividly’. Ekphrasis was first practiced by the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos. His words “poema picture loquens, picture poema silens,” were translated as “painting is mute poetry, and poetry a speaking picture.” Horace’s famous statement of “ut picture, poesis” , a Latin phrase literally meaning “as is painting so is poetry” in his Ars Poetica became the motto emphasizing the bond between the verbal and the visual. Even though poetry and painting, which make us see and read respectively, are considered to be sister arts, they are also rivals. Poets rework this old tension between looking and reading, the urge to understand the relationship has continued since antiquity. Therefore, we can see a series of reverberations between verbal and visual material in nearly every century. Ekphrasis has strengthened its place in today’s literature as an established tradition because the question of the nature of representation dominates twentieth and twenty-first century philosophy and literary theory. Indeed it has become a tool of subverting hegemonic ideology and social structures.

The word ekphrasis has been variously used and defined for centuries according to different literary conventions and tendencies. Nevertheless, one of the most acknowledged definitions of ekphrasis belongs to James A. W. Heffernan, who defines the term as signifying “…the verbal representation of visual representation”. Ekphrasis in contemporary poetry and literature talks back to, indeed deconstructs, phallocentricism, among others, and opens space for change.

Verbal engagement with paintings and painters via ekphrasis dates back to antiquity, Homer taking his place among its first practitioners. Now, the postmodern understanding of a subversive ekphrasis overlaps with the use of postmodern intertextuality, which is equally deconstructive. Women poets engaging with and rewriting ekphrastic poems draw attention not only to the role of the image as other to the word but also women’s role as the other that must be regulated by and in words. As W. J. T. Mitchell stresses, “The central goal of ekphrastic hope might be called ‘the overcoming of otherness.’” The poet’s process of reading visual codes of paintings and transforming them into poems is, in a sense, a kind of struggle for the dominance of the word over the image. Thus it can be argued that ekphrastic texts disclose a rivalry, a struggle for power.

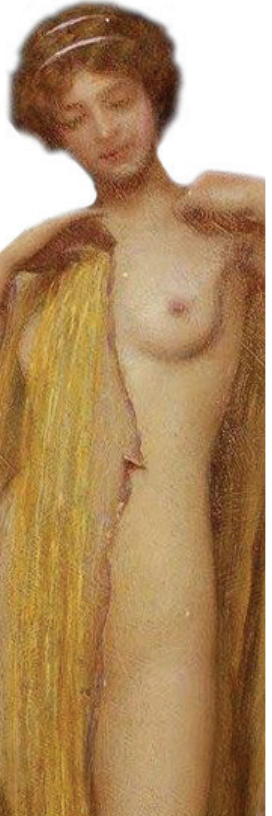

In ekphrastic poetry, the image is the other of the word, indeed is in a sense appropriated and translated into it. The female (body) is another other in the male dominated ekphrastic tradition. Indeed, it has to be stressed that the power struggle at the heart of ekphrasis “is often powerfully gendered: the expression of a duel between male and female gazes, the voice of a male speech striving to control a female image that is both alluring and threatening, of male narrative striving to overcome the beauty poised in space.” The women poets explore this power struggle and the male gaze’s attempt to regulate and control the female (body) by contemplating canonical nude paintings. In these paintings, the naked female body traditionally depicted by a male painter seems to signify the essence of a femininity which is both alluring and threatening. The male gaze thus seeks to convert the female body, an overpowering physical presence, into a framed, frozen and hence less threatening object.

The female model is under the gaze of the artist and the viewer, both identified traditionally as male. In cinema studies the spectator is defined as male and the object of his gaze as the female spectacle that is regulated and consumed by him. Laura Mulvey stresses that: “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearence coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”

As part of the creative process, the model poses for the male artist. While posing, they are expected to remain motionless, and silent. Berger, explicating this traditional idea of a female being looked at, or gazed upon, states similarly to Mulvey that: “men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

The gaze, then, grants authority to the male viewer, the act of looking thus involving mastery and possession of the object, the female body. However, in order to gain absolute control, the gaze of the male painter must turn the female body, apprehended as an unruly, thus a threat to male civilization, into a painting, often a portrait or nude painting.

The tradition of portrait painting gained momentum in the Renaissance when the human being began to occupy the centre of the universe. There emerged the tradition of painting individual portraits within this period that described the sitters’ wordly position, identity, wealth and social standing. Portrait painters traditionally aimed to depict not only the physical appearence of the sitters but also their inner lives. However, female sitters, wearing costly jewellery or lace and conveying an expression of submissiveness by their gaze and bodily posture, were often also meant to signify the economic and political power of their fathers and husbands. But the male painter’s struggle to control the female body and force it into submission is much more evident in nude paintings.

The female nude has always been popular in male dominated art/history. Painters of the female nude were traditionally men since, in the past women painters, whose numbers were limited, were excluded from studies of naked models, male and female, on the ground of social decorum.

Although the image of the female body within a frame became a symbol of civilization, this body was disempowered and vilified. Servants, prostitutes and poor women were chosen as nude models. Since posing as such was considered disrespectable, it was only these women at the bottom of society that were ready to serve as nude models for usually little pay or in the case of many servant girls no extra pay at all. To be depicted as naked rendered them even more powerless. As they were deprived of their clothes, which are markers of social status and identity, they were deprived also of their classes, their identities, and their subjectivities. These models were usually the anonymous unacknowledged subjects of paintings.

The female body, indeed the body per se, was moreover vilified in western culture. Beginning with Descartes, the thinking subject was thought to be disembodied in western ideology. Christian and Cartesian thought rejected the body as signifying a void, nothingness, even worse, a fallen state, deception, dirt, and sin. There was a constant denial of corporeality and an elevation of mind or spirit. The body occupied the place of the excluded other.

However, as Kenneth Clark states, in order to assume absolute mastery, the male painter must turn the naked body into a nude painting. Clark, commenting on the differentiation on the naked and the nude, argues that the nude is the elevated body in representation, the body produced by culture, a form of art contrary to the naked body without clothes that is linked with dirt and the disorder of formlessness.

Margrit Shildrick and Janet Price point to the male’s construction of “the female body [as] … intrinsically unpredictable, leaky and disruptive” and therefore as “… out of control, beyond, and set against, the force of reason” and “conteminat[ing] and engulf[ing]” As Lynda Nead points out, above the female body must thus be transformed into an aesthetically pleasing artistic image. The naked female body is in a sense dressed. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger indeed remarks that “Nudity is a form of dress”; rather than seeing it as a dress that conceals the supposedly vile naked body, he speaks of nudity as a dress objectifying and thus rendering the naked figure visible in culture, however, at the price of forcing her body into submission.

The painters struggle to assert mastery over the female also involves sexual possession. Anna C. Chave states that “Conventionally, both the act of painting and that of viewing have been described as phallic acts, acts of penetration performed on that passive receptacle, the blank field of the canvas.” The artist’s obsession with transforming the naked female figure into a regulated art object is inseparable from the physical attraction he feels towards her, as if the sexual relationship between a male artist and a female model were a condition. Actually Martin Postle observes that in “Victorian England, (…) the female model was synonymous with prostitution.” It strengthens the idea that to initiate the artistic enterprise, the object must first be sexually possessed, the brush of the male painter being also his penis. What Gilbert and Gubar assert about the male writer as also applicable to the male painter: “Male sexuality is not just analogically but actually the essence of literary power. The poet’s pen – in this context his stick – is in some sense a penis. (…) In patriarchal Western culture, therefore, the text’s author is a father, a progenitor, a procreator, an aesthetic patriarch whose pen is an instrument of generative power like his penis. The notion of ownership or possession is embedded in the metaphor of paternity. Thus because he is an author, a man of letters is simultaneously, like his divine counterpart, a father, a master or ruler, and an owner: the spiritual type of a patriarch, as we understand that term in Western society. ”

The male painters’s sexual possession of his female model is an act signifying the colonisation and exploitation of the female body, thus inviting the idea of an ideological battlefield. He is the one who controls the brush, colours, perspective and the female body. This analogy between artistic creativity and male sexuality also evokes the notion of the artist as a male genius. Feminist ekphrasis now is on stage in order to deconstruct this historical oppression in the art works and the cult of the male artist.